|

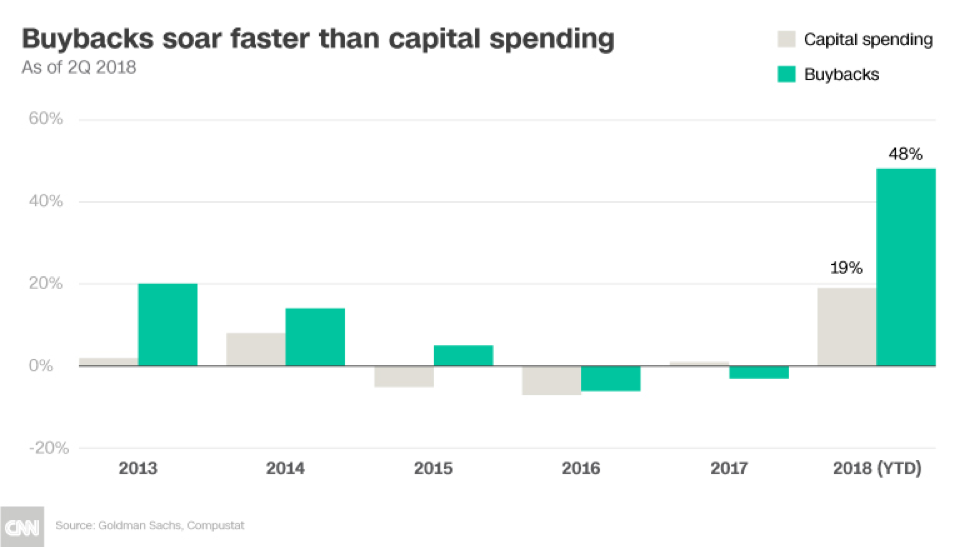

A quick search of our good friend Google will reveal multiple pages of results wherein various experts will opine about the failure of companies to innovate (while alternately cheerleading those that do (or give the impression that they do)). While true that more and more companies are investing in innovation incubation, this incubation surfaces in a variety of forms. In some cases, it appears as dedicated time to work on new projects apart from the day-to-day (Google made this approach spuriously famous), while others are creating dedicated organizations to drive new products and business models (the Ford/IDEO collaboration). Not to be outdone, seemingly every consulting organization on the globe has created an innovation playbook (including my former employer) with a step-by-step guide to fostering a culture of innovation. However, for all the talk and showmanship, much of this fabled innovation is vaporware, floating discordantly in a vacuum of its own creation, never to see the light of day, while some “innovations” are fraudulent from the start. Often even legitimate innovation initiatives limp to market only after being beaten half to death by the operational realities of the company, with each step of the development cycle slicing off a pound of flesh until what remains is a pale reflection of the original intention. There are many, many reasons this happens, and these failures often reflect the absence of internal capabilities to successfully deliver to market (people), a lack of organizational readiness (process), and technical deficits that prevent the realization of the product or service (technology). I don’t intend to add to an already oversaturated field of expert opinion on the subject of innovation. The failings of companies to innovate are often rooted in their failings to operate effectively in their current environments (the threefold people/process/technology conundrum above). As corporations have grown cumbersome and unwieldy, a number of reasons exist to inhibit effective innovation, but I shall endeavor to point to one culprit, that at the very least has enabled the others: stock buybacks. Although stock buybacks are very much in the news in the wake of the Republican tax cuts and soaring corporate profits, they’ve been around for a while now. Although never explicitly illegal, stock buybacks remained taboo for nearly half a century (for good reason) until the Reagan-appointed head of the SEC, John Shad, introduced a new rule that essentially gave companies free reign to go nuts. If you’re a billionaire investor or the head of a major corporation, then this has worked out pretty well for you. If you’re pretty much anyone else, then maybe not so much. So, what do stock buybacks have to do with innovation? Easy: stock buybacks divert capital spending away from reinvestment in infrastructure (technology), wage growth and the ability to attract and retain talent (people), and sustaining a culture long-term strategic thinking and enablement (process). For those of us working in these organizations, many of our collective woes stem from one, if not all, of the above. And although we’ve seen moderate increases in capital spending in the wake of the 2018 tax cuts, they pale in comparison to the amount being directed towards the buybacks. Those of us on the ground in the design and development realms are often starved of the capabilities necessary to effectively deliver the experiences we design to market (yet are held accountable when they fail to deliver the intended financial results). You’ve likely encountered this in your own work, where great products and services fail to launch (or scale) due to a lack of available infrastructure – manifesting as disconnected systems, siloed architecture and data structures, lack of organizational agility, or absence of the required skills to realize the vision in an increasingly complex environment. The punchline in all of this is the chief executive who rants and raves about their organization’s ability to deliver “innovative” products and services while redistributing capital to investors (and themselves).

Further, buybacks reflect the cultural deficits currently at play in America, where self-obsessed investors, who produce absolutely nothing of value, have an increasing amount of control over the destinies of major corporations and profit on the backs of the workers. These investors, who seek only immediate returns for their investments, stifle innovation (or the ability to effectively deliver on innovation programs) by encouraging (in the Game of Thrones sense) companies to prioritize the short-term at the expense of long-term strategy. None of this is tenable. The average lifespan of an S&P 500 company in 1950 was 60 years. Today it is around 20 years, and by 2027 it is expected to be 12 years. Of course, investors don’t care – they’ll move on to the next thing like the parasites they are. For the rest of us, this poses significant problems for our future stability. Remember this the next time your leadership criticizes your ability to innovate. Remember that they are the one actively redistributing the resources required for you to do so. And they’re making a killing doing it.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

EldridgeI'm alternately fascinated, appalled, and enthralled by the intersections of society, technology, and business. Archives

September 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed